and Clive Sinclaire

(ex Wheeler)

ADAPTED FROM THE “INTRODUCTION” OF A STILL TO BE PUBLISHED BOOK

December 1963 saw me leaving school and coming into the real and exciting world. Gone now was the security and comradeship to be found at Kings School, Sherborne and new and unknown situations faced me. It was not altogether daunting as I was thrust headlong into the “swinging sixties” of London, where anything was possible.

School had given me an appreciation of oriental art, mainly through my closest friend, a certain Lee Chuen Pee, more conveniently known as Charlie Lee. Charlie was an interesting individual whose father in Kowloon was a director of the powerful Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. He had sent Charlie to an English boarding school with the sole intention of him learning to read, write and speak the English language. This was completely beyond Charlie who would have gained a master’s degree in pigeon English but was barely understandable to anyone else. As his mission was to pass at least one exam in English, he learned huge tracts of literature off by heart and adapted them to any exam question that came up. For instance, if he had learnt “Casius’s lament” from Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar”, and the question was about the weather, he would liken Casius to a stormy day and to then go into a pre-learned diatribe about Casius!

Notwithstanding, Charley had things to teach me. He was a superb traditional pen and ink graphic artist. His subjects were usually epic Chinese battle scenes with hundreds of figures each individually drawn in microscopic detail and over them all, huge dragons in the sky with every single scale drawn. He had reference books that I also started copying and these were invariably warriors with great halberds and swords, their robes flowing and with grim and frightening expressions on their faces. These pictures, together with late night kung-fu lessons in the dormitory, now set me on a life-long appreciation of the alien warrior culture of the Far East.

Being of slight build but pretty fit, there were a number of sporting activities that suited me. At school I had been rather good at cross-country running, 6 miles being my best distance, but as this was mainly a device to get me out of the school grounds and past the local cigarette shop, it now lacked the urgency and appeal it once had. My position as 1st fifteen rugby captain at school, had helped secure me an advertising job in the multi-national company, Unilever (the manager who interviewed me was also a local rugby coach and was short of a scrum half. He said “if you can turn out to play on Saturday you can start work on Monday”!). The pay was only £410 per annum but it was the only job on offer and I was about to become homeless so I accepted and played scrum half on Saturday. I began playing club rugby regularly and started to learn how to manipulate and negotiate media schedules. However, with the kung-fu background the appeal to join the Unilever Judo Club was irresistible. I turned out to be quite good at judo, at one time training 5 nights per week.

My “legacy” from Kings School was an enduring appreciation of oriental graphic and martial arts (I still teach) and a respect and admiration of English literature as well as an ability to write. These latter two were due to the teaching of Peter Thomas, to whom I am eternally indebted.

Link to pictures of Clive and Charlie Lee

I also dug out this picture which has me (the handsome crouching one) Charley and Crump in the same picture

| Clive Perkins, Charley Lee and Clive Sinclaire (ex Wheeler) |

|

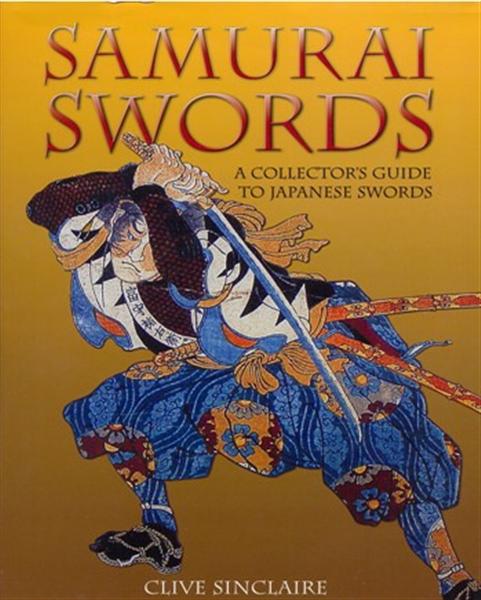

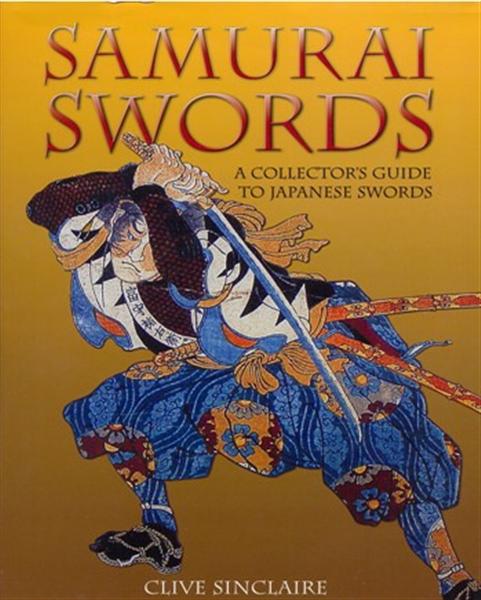

The Book! |  |

|

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The bug of the oriental warrior with his great swords and halberds first bit me at school. Here, a close friend named Lee Chuen Pee, a Hong Kong Chinese, was a very skilled drawer. His subjects, mostly in pen and ink drawings, were the heroes of feudal China drawn in microscopic detail. He drew panoramic battle scenes with skies full of dragons, and I was fascinated by this alien martial culture. On leaving school, I took up judo and it was easy to further develop this interest towards the warriors of Japan, the samurai and their weapons.

PRESERVATION, SHINSA, POLISHING

Swords come to collectors in many varied and often distressed conditions and it is beholden on the new owner to preserve and restore the sword to the best of his ability, although sometimes it may be considered that restoring the sword is not a viable option. I have recently added swords to my collection that are "write-offs" to all intents and purposes.

One that particularly springs to mind was a sword that was given to me by an old school friend. It had been in his father's loft for some sixty years. This blade, minus its tsuka (handle) was in a wooden saya with a rather bulky, leather foul-weather cover and had come from the Burma Campaign of 1945. I suspected that under the leather outer cover might be a lacquered saya of some interest, and I decided to remove the leather. To my surprise, under the first leather cover was a second one. However, about midway down the "package" were two strips of bamboo, each about six inches long, which were bound to the second leather cover with thread. It looked like a splint, and I immediately expected to find a broken saya underneath all this. On removing the splint and the second leather cover, I encountered a thin linen or muslin bandage, which I unwrapped to expose a beautiful black-lacquered saya that was ribbed in the inro style. As expected, however, it was broken in two, and the bottom quarter was of plain wood that was also wrapped in linen and held securely in place by wire binding!

The blade of this sword had been badly abused and had lost much of its monouchi, while the hamon and jihada were not visible. The mekugi-ana had been enlarged and a nut and bolt put through it, but an indistinct two-character inscription on the rusted nakago read: "Norimitsu." (Norimitsu was a talented Bizen swordsmith from the 15th century). To top it all, there were at least two ha-giri (hairline edge cracks)-a serious and irreparable flaw!

Obviously, a sword such as described above is a relic that has little collectible or commercial value, and it is hard to justify spending money on restoration. However, it occurred to me that I was probably the first to see the lacquered saya in over sixty years, and the deceased Japanese owner may have been the previous one. There is no doubt that the sword had had a tough life. I thought it was highly probable that the original Japanese owner had taken an old family sword onto the battlefield and that the extensive saya repairs were probably field repairs, maybe even done by him. It seemed that this owner had highly rated the sword and saya and had gone to a lot of trouble to preserve it under what must have been extreme conditions. I felt that, if only out of respect for the Japanese owner, the sword certainly deserved to be cared for and preserved. After repairing the break in the saya with a modern adhesive, I resolved to keep it in my care for these somewhat "sentimental" reasons.

The sword showing the black lacquered scabbard containing the blade. The round disc is the tsuba or iron hand guard

Clive Sinclaire (ex Wheeler)

January 2010