Part 1

Fees

Should I commence with something so sordid? Perhaps I should, as money had to be a serious matter to JHM. A bill in the archives shows that in 1959 fees for Boarding and Tuition for a Fifth Former were £99.10s per term, with Extras nearly £14. A 1963 Schools Directory in my possession shows annual fees at Public Schools ranging from £400 to £500. There was a suspicion that parents of boys from abroad received larger bills and we surmised that some of these were paid into what are now known as off-shore accounts!

Before going to University I did a "gap year" at JHM's accountants in Cheltenham. JHM fixed it up for me and care was taken to ensure I had nothing to do with the K.S. account. I was paid £2 a week and only now have begun to wonder if JHM got a commission from my employers! I remember the chief clerk being wryly impressed by the way in which at Sherborne all string on parcels had to be untied (not cut) by the recipients to be collected for re-use. This next bit you will not believe. Whilst I was with the firm one of the two partners got into serious trouble for endorsing fraudulent tax returns and some months after I left the other did too. It's a long time ago but I think both went to gaol!

At that time audio-visual equipment was unheard of and printed books and source material very unattractive so that successful learning depended almost entirely on the skills and input of our teachers. In that regard we were not ill-served. With relatively few exceptions they were adequately qualified and competent. Geoff Perry, of course, became something of a national, perhaps international, celebrity with his establishing of the Sixth Form satellite-tracking group at Kettering Grammar School in the early days of the space race. Mr. Thomson (History) did stay with us for about five years but that seems to have been the record. Some staff showed conspicuous dedication and could be inspiring, but rapid turnover (eg. In French where in one term we had three teachers) and poor classroom discipline could be problems.

It was difficult to understand why the school, which at times trembled under the stern rule of the Head, could have such uproar in lessons. One would have thought that the mere threat to send a miscreant to the Headmaster would have quelled indiscipline immediately. I can only conclude that JHM's regard for firmness and independence extended to the staff and that he expected no one but themselves to maintain classroom control and so forbade them the easy option of appealing to his formidable powers of repression. The result was that lessons with certain unfortunate teachers became relished opportunities to let off the safety valve and chaos regularly developed on a grand scale.

There was too a lack of academic ambition and of intellectual stimulation, and little encouragement to think any further ahead than scraping together a few "O" levels. The library, such as it was, consisted of a couple of shelves of books, mainly modern fiction, the most popular being books in the Hornblower, Swallows and Amazon and Just William series, with a few war memories such as The Cruel Sea. There was no reference section and very little non-fiction. The school had no Sixth Form, though to be fair (and that's another story) I was able to pass some "A" levels whilst still at Kings. A few other students after leaving at 16 did go on to higher education, in at least one other case (BM) with considerable distinction.

Another difficulty was the presence of boys from abroad in normal classes. The "foreigners" as we called them (with none of the prejudicial over-tones that the present PC crowd would abominate) probably got a very good deal at the school. Thrown into a disorderly mob of British school kids, they very soon picked up the language, even though some arrived with a very scanty knowledge of it. Needless to say, the first terms they picked up were the swearing and coarseness of schoolboy argot but in the course of three or four terms they mostly became good speakers of English, though I don't know how far this extended to their command of written English. The small size of classes (about 20) should have been beneficial to all pupils but the presence in the more senior forms of several foreign boys who for the most part were not taking "O" levels could pose problems for teachers of focus and control.

One curiosity worthy of mention was how a few boys over the years seemed to be able to please themselves as to whether they attended lessons. These were the pupils who were entrusted with looking after the chickens or operating the Allen's auto-scythe or Ferguson tractor in the absence of any Health and Safety considerations! I remember two classroom choruses, as the tractor passed the window; "Hats off to Fergie!" and, in answer to the teacher's vexed question as to a pupil's whereabouts: " 'E's veeding the vowls, sur!"

Sport and Leisure

In the early 50's, towards winter with the days getting shorter, the schoolday was reorganised so that from Monday to Friday there was a 60 minute period of compulsory games after lunch. The afternoon lessons immediately followed, though split for a break for high-tea that was closely followed by the last afternoon lesson and then prep (i.e. homework). The system certainly made the best of the daylight but we had virtually no free time during the whole of the day apart from the 20 minutes of morning break. It could not have been popular with staff.

Indoors we had billiards, snooker and table tennis. There were also activities such as play-acting, debating and aeromodelling. A mean and bizarre practice was to make a small charge for the use of certain facilities. We were told this was to teach us the value of money but a degree of hypocrisy operated here because it was clear from the scale of receipts that pupils were spending far more than could possibly have come from the official weekly pocket money issue of one shilling and sixpence. Recovering lost property also came at a price.

A copy of "The Telegraph" was available in the library and, though the school supplied no radio, many boys had portables. TV was in its infancy but Mr. Chadwick had a set in his room to which over a brief period he invited small groups of 3 or 4 boys at a time, presumably to marvel at this new invention. Teachers, unsurprisingly, were not encouraged to socialise informally with pupils. In the winter months JHM gave a fortnightly film show in the Hall, which would comprise an old feature film and a number of shorts including his own movies of activities at the school. Annual treats such as the Christmas Party and Guy Fawkes Night were much appreciated.

There were other projects too, sometimes compulsory, such as the work on the swimming pool, various garden and grounds activities etc. Cycling in the locality was popular too with some boys venturing much further afield than officially permitted. Another outstandingly successful group was the Scouts, led by Mr. Thompson. Several boys attained the King's Scout Award.

Organisation and discipline (Part 1)

Occasionally there was a collective punishment. At Weston-Super-Mare, before the move to Sherborne, my dormitory of ten eight to nine year olds each received two strokes of the cane for persistent misbehaviour after lights out. One collective punishment involved the whole school. Someone had maliciously cut some inter-com or telephone wires near the Staffroom. We were all assembled in the Hall before lunch and the perpetrator ordered to own up, which he didn't. We were kept standing in the Hall until sent off, lunchless, to afternoon lessons. When we went for tea we discovered it was to be the plates of stew and veg, which had been set out some three hours previously. Not surprisingly no-one ever admitted responsibility for the offence.

In many ways JHM seemed to regard the five or six senior boys who were appointed Prefects as more effective or reliable than some of the teaching staff, and, answering directly to him and with his close authority behind them, perhaps they were. They therefore carried a heavy burden of duties and responsibilities, the most irksome of which was having to supervise a class during prep (ie homework) when one probably had rather a lot of work to do oneself. JHM often gave the impression, perhaps deliberately, that he set more store by the prefects than by many of the teachers. Of course, he didn’t have to pay any salaries but he and Kathleen Mosey seemed to acknowledge something of a debt when at the ends of the 1953 and 1954 summer terms they treated the prefects to excellent dinners at what were regarded as highly reputed and expensive hotels at the time, the Lygon Arms at Broadway and the Shaven Crown at Shipton-under-Wychwood.

At one stage classroom order had so deteriorated that JHM authorised the teachers to use the cane. Few did so but I remember two ludicrous occasions. In one I was punished by Mr CAB, quite deservedly so, but his room was excessively narrow and being a bit careless with his backlift he managed to knock a pottery ornament off the mantelpiece. The other occasion was a dark evening when Mr B, a very decent, kindly, tolerant man, had finally been driven to distraction by RH, the chicken-keeper. The news spread quickly and a number of us crowded into the darkened washroom which was on the first floor and from where we had a grandstand view of Mr B’s room across the inner courtyard. Suddenly it was illuminated as bright as a stage in the theatre. Mr B had entered, followed reluctantly by H. There was a large table in the middle of the room. Mr B exits right for a moment, then reappears brandishing a cane. H sidles round to the opposite side of the table. Everything happens as though in a mime show. Beckonings and cane-wavings by Mr B, determined shaking of the head from H. Mr B tries moving quietly around the table but H reciprocates, keeping the table between them. Mr B tries the other way but H does too. Mr B tries to rush around the table but H is too quick for him and maintains his distance. Eventually after further ineffectual feints and lunges Mr B seems to lose heart, his shoulders droop and he seems to address some earnest words to H. H nods his head submissively, then exits. Mr B turns towards the window and draws the curtains. End of scene: no caning.

I do recollect the one public caning only too well. It was far from edifying. Two boys M and F aged about 10 had been forever in trouble and no sort of sanction had worked. JHM assembled all the pupils in the Great Hall with the boys and himself halfway up the stairs on the landing below the Quarterdeck. I cannot recall the other teachers being there. JHM was wearing his big black gown as he generally did in assemblies and lessons. He grasped the wrist of M, a small skinny boy who had joined the school only recently. He then proceeded to thrash the small hand with six very powerful strokes. Almost immediately M started literally to scream for mercy. His pleas went unanswered. I can still see the high upward movement of the cane, the swirl of the gown, the small white hand with the fingers spread wide, and the cane whistling down with a vicious smarting crack across the palm. I think we were all pretty shocked but to our surprise and perhaps horror after those six sickening strokes JHM seized M’s other hand and, despite the piercing wails, inflicted another half dozen blows with energy unabated. He then released M. who stood there whimpering, rubbing his hands fiercely together to alleviate the stinging pain.

All this time F had stood there stoically watching the execution. JHM now turned his attention to him with exactly the same style and ferocity as before. F was always pale of complexion and may have been even paler now but he made neither sign nor sound that would betray his feelings. After six strokes JHM turned his attention to F’s other hand. Whether tiring or discouraged by this lack of response JHM’s next six were not administered with anything like the power of the other. He released F’s wrist and said for all to hear: “I admire you, F.”

So what can we make of all this? I don’t think there are any easy conclusions. We were all shaken and shocked. I personally would not recommend such a spectacle for anyone but I just don’t know if the experience had any serious longterm effect on myself of others. Were we unduly cowed by this scene and forced into a kind of self-repression? Did we develop an unjustifiable acceptance of authoritarianism? Did we become bullies, sadists or masochists? More importantly, as for the victims, what can one say? Not surprisingly M was in no more trouble in the remaining weeks of term but he did not return to school afterwards. F stayed at school until after I left. He did not seem to lose any of his spirit or energy but from this time on they seemed to be more positively directed. He did not become a toady or a goody-goody but remained popular and respected by his peers and was a very successful prefect, carrying on his duties successfully through the simple force of his goodnatured personality. I don’t think he’s made contact with us in recent years but he seems to have had a successful career as a professional actor.

This is the only public caning that I witnessed. (To be continued)

Organisation and discipline (Part 2)

Smoking, of course, was a great matter in those days, accentuated by the irony that most male members of staff smoked, not least JHM himself. That subject would merit a section in itself. Anyway, JHM was assiduous in his pursuit of smokers and would often threaten his ultimate deterrent: a pipeful of old naval shag such as used by his sea-faring grandfather (another section is called for!).

He never did invoke this major sanction until one day we couldn't believe our luck. _ _ _

A boy of about 15 had joined the school. J came from Iceland and, perhaps it was the long dark winters, but he was easily the worst tobacco addict I've ever known. I have no idea from where he got his cigarettes or the necessary money but his fingers were bright orange, rather matching his carroty hair colour, and he was forever in trouble over his not so secret vice. Eventually - and, remember, we'd waited years for this - JHM declared that J would in front of the assembled school consume a pipeful of old naval shag. We were all agog. When you're only thirteen or so, the sight of someone vomiting into a bucket is a pretty inviting experience. So, there we all were with J seated on a chair on the stone-landing in the hall, a bucket next to him, and JHM displaying a brand new pipe and a packet of very dark and oily baccy. JHM tamped a good wad of it into the pipe, handed the pipe to J and with a flourish produced a lighter.

Soon the baccy was lit and a heavy oily smoke began ascending. JHM stood there triumphant, awaiting the successful outcome of the demonstration. We all strained forward trying to detect a slight change in J's complexion, which was pretty pale at the best of times. He continued puffing. Eventually we started to feel a little bored. JHM's stance was not quite so confident. He shifted his weight from one foot to the other. J was still puffing steadily. It began to dawn on even the slowest of us that J was enjoying this smoke. Believe it or not, the whole school had been assembled to watch him enjoy a pipe of tobacco. JHM was in a quandary. This could take a long while and lessons should be starting in ten minutes or so. J showed no sign of distress. Eventually it was J who got us out of the fix. Perhaps he was feeling just a little queasy but I suspect he thought he should put an end to the performance. Taking his pipe from his mouth, he leaned over to the bucket and made a small deliberate spit into it. JHM seized the opportunity. He had the pipe out of J's hand in a jiffy. "Now let that be a lesson to you, J." he said and lost no time in dismissing us. J should have got a lot of prestige amongst us from this incident but he seemed a sad lonely boy. The term ended soon after and he did not return after the holidays, though I think it could not have been due to this incident. JHM never again used the old navy shag deterrent whilst I was at KS.

Still, despite the best efforts of the disciplinary system, we found a lot of ways round it. Just to mention a few: bike trips into forbidden distances to visit shops, meet girls, etc; purchases of Woodpecker cider at the Taylor's village shop; dormitory feasts; betting on games of snooker or table tennis; crawling under the floors through the dusty ducts of the former Victorian heating system, perilously climbing out of the upstairs windows; midnight sledging; poaching. No doubt there were others. After my time some entrepreneurs got hold of some of Lord Sherborne's property and flogged it to a Burford antique dealer. Schoolboys, thank God, are irrepressible.

Care

No-one could forget the arrangement over butter. We each had a small glass bowl in which half-a-pound of butter appeared on a Saturday, covered by a small muslin cloth on which one's name was written in indelible ink. (If my memory serves me correctly by the time I started at the school in 1951 the 'butter ration' had been reduced to a small piece of butter atop a larger piece of margarine. Ed) That was the week's ration for breakfast and high tea. Few managed to stretch it out and George Young didn't even try. He'd finish it by Sunday. I can see him now splitting the very bready sausage of that period and inserting a thick wedge of butter. In the summer with no refrigeration the butter dishes had a strong rancid smell.

Tuck, of course, was an important feature of our diet and the weekly sweetshop, administered by prefects, very popular. On Tuesdays and Thursdays we had only a bread-and-butter tea and were expected to supplement it from the contents of our tuck tins. This was not good news for those few boys who rarely received parcels from home. Supper was a convivial buffet taken at staggered times in the evening and usually consisting of cocoa with slices of bread, margarine and marmite.

Living in a nineteenth century mansion was a privilege and boys seemed appreciative. The decorative condition was good and stayed that way as it was generally treated with respect. The Hall had been handsomely refurbished in the late 40's and Sherborne family portraits in the Hall and Dining Room helped embellish our surroundings. I cannot recall a single serious act of vandalism. Few areas were out-of-bounds, the main one being the Hall which was used only for supervised gatherings of the whole school. Most dormitories were pleasant enough with only eight or ten beds to a room but the exception was Big Dorm, the former Ballroom, which held about 40 occupants (in later years more when bunk-beds were introduced. Ed). Some unfortunates were based there for all their years at the School. It could be very cold in frosty weather though the rest of the building was tolerable with the cast-iron central heating system. The energy bills must have been formidable. It was not surprising perhaps that JHM sometimes went ballistic on finding an outside door open.

Personal hygiene was not the same as today but we seemed none the worse for it. We had a perfunctory wash on rising at 7:20 am, there were hand inspections by the prefects before meals and we had a good wash including the use of a footbath before bed. Apart from showers after games in the winter we had a once-a-week bath rota. There was a weekly change of shirt, socks and underwear, as far as I remember. Blazer and flannel trousers served the whole term though there could be another suit and perhaps a shirt on Sundays. Bed linen was changed fortnightly. Sportswear had to last all term. There was a drying room to hang it in but I'm not convinced anyone washed it beforehand. When I got home at the end of term my mother would immediately destroy my football socks.

Anyone feeling under the weather could visit the dispensary after breakfast where the School Nurse treated most ailments with a small dose of quinine. Occasionally someone might be admitted to the Sick Bay where there were four or five beds.

As for our spiritual or psychological needs the School met them in the very limited way that was common to most secondary schools. We had a daily religious assembly led by JHM, a weekly RE lesson and once a fortnight we attended the morning service at Sherborne Church. I remember nothing of what now passes as Pastoral Care in modern schools but in such a small community we were very well known if not well understood, by the Moseys and the rest of the Staff. Several OB friends of mine say that they found JHM most sympathetic and supportive when they had problems at home and KS provided a valuable refuge.

Just how happy were we? Is happiness the primary object of education? Looking back I think I got a lot from the School though not enough to have wanted to send my sons to a similar establishment. I do remember once when I was a senior pupil, having heard that as we get older we tend to regard the past through pink-tinted spectacles, that I told myself there and then that I should never forget that I was not happy there. It isn't easy now to remember what was bugging me. Some of it may have been absence from home and I am sure that another problem was the considerable burden of responsibilities and duties that senior pupils carried. And yet there was a lot of fun and friendship, not least in the camaraderie of the community. I didn't send my sons to boarding school but I still think a few years of weekly boarding in one's teens, perhaps at a co-ed establishment, would be the ideal solution.

As for the other nurses in the photos, others in these pages have claimed that Nurse Pyatt married Mr Maw (PE), who must not be confused with his predecessor in PE (Dickie Moore),and that Nurse Boughton married Mr Breach (History, not Geog usually, as surmised by John Haymes). King’s School must therefore have played a part in some romantic liaisons, which makes it all the more surprising that little “Lottie” Loxton and Nurse Harding, pretty and sympathetic young ladies both, seem to have escaped entanglement whilst there!

Now a couple of responses to points raised recently. Firstly, there were many aircraft brought to Little Rissington aerodrome prior to scrapping after World War Two, some of which even had to be parked in the neighbouring fields. I think the majority were Wellingtons, the two-engined aircraft designed by Barnes Wallis that was the mainstay of Bomber Command in the very difficult early days of the War, also known affectionately as the Wimpey.

David Wright asks about a school hymn. I don’t think we had an official one, though every morning we sang something from “Songs of Praise”. At every last assembly of term it was “Jerusalem”, rendered with gusto, as you might expect, and of course, if the night had been windy, in an obvious gesture towards Mosey’s claimed sea-faring ancestors, it was inevitably “Eternal Father strong to save…” For similar reasons the reading was often the text “They that go down to the sea in ships and have business in great waters.”

John Haymes reports that he worried about failing to give me my cue in Peter Pfaff’s production of “Ten Little N***ers” though this title is no longer considered ‘PC’ [It has since been titled “Ten Little Indians” and “And Then There Were None.” Ed.] He needn’t have worried as it must have been mightily overshadowed by my appalling blooper at the very climax of the final scene. By then eight of the ten characters appear to have been bumped off which, disappointingly for the audience, leaves only the male and female leads surviving, so one of them must be the killer. (The two performers in the KS production were later to reach senior rank in the RAF as pilots of fast jet and V-bombers respectively!)

So the would-be lovers confront each other in a mixture of fear and suspicion, in what should be an atmosphere of great suspense and emotional intensity. It goes something like: “So, there are only the two of us left now…” “Yes, just you and me. There can be no-one else on the island.” In our production at that precise moment a hand suddenly shot through the unglazed window of the room they were occupying and made a desperate grab at the window shelf. A split second later came a sound like a bomb going off.

The culprit was myself, playing the crafty murderer who in fact had not been bumped off earlier as was thought. I had been manoeuvring to make what should have been a sensational entrance through the door lower right, access to which was by way of a trestle table (Health & Safety again!) Unfortunately I stepped off the midway stone platform at the end of the Hall (where the stage was) on to the end of the table top which reared up, threatening to deposit me in a heap on the stone steps, so I shot out my hand in a desperate hope to grasp some part of the scenery and, in recovering myself, I brought the table top down on its metal trestle with a deafening crash. It rather gave the game away!

By the way does anyone remember and can they identify a car Pete Pfaff drove? Most teachers in those days didn’t have cars, though there might have been the odd motorbike. Chris Marx recalls Mosey’s rather nice early 30’s Daimler, later replaced by a new Standard Vanguard, and Chadwick (retired industrial chemist) had a pristine pre-war Vauxhall saloon; but I distinctly remember standing with others on the running-board of a large pre-war tourer, driven very slowly by Pete, as we conveyed large scenery flats from the Stable Block to the main building for the play. It could have been an American vehicle.

James Harold Mosey, Headmaster and Teacher

Another youth was not so lucky, though only he and JHM were witnesses to the incident. Pryke had been running along the first-floor corridor towards the Ship staircase (“no running in corridors” was a cardinal rule). JHM had come out of the Mosey flat which was just around the left-hand corner and a collision occurred which seriously disarranged the boy’s nose. The incident was presented to us as the sort of accident that can occur if people run down corridors, but Pryke’s account and the seriousness of the injury suggested that there was deliberation on JHM’s part. Indeed, Henry Forti’s recent anecdote concerning this matter is more specific on the details than mine. Strangely no questions seem to have been raised by Pryke’s people but his facial appearance was definitely altered.

Such incidents were mercifully few, though I have mentioned earlier in my anecdotes section that JHM was a formidable disciplinarian who was not averse to using corporal punishment, though the number and manner of canings were probably not excessive for the 1950’s. On one occasion he caned no fewer than a dozen boys who had been removing bits of equipment from the redundant aircraft parked in the fields around Little Rissington aerodrome. The miscreants were punished one at a time during the course of our afternoon high tea, the door between his study and the dining-room regularly opening to admit a rueful-looking youth. At the end of the meal the teacher on duty intoned, “For what we have received may the Lord make us truly grateful,” and all could hear quite clearly the sound of the last caning being administered. This was closely followed by the entrance through the door of Hazelden, grinning sheepishly, one whose regular offences and their inevitable consequence had made immune to corporal punishment.

On the whole JHM practised his strict disciplinary code with a degree of fairness but others have mentioned some unpredictable reactions on his part. I recall one great injustice suffered by Otto Lai-Kiaow, a bright and lively lad from Trinidad. Otto was a prefect and a popular and effective one. One evening, as a sort of joke and being a bit short of something to do, he filled in a postcard as an entry in a competition for small children in the “Daily Telegraph”. Without paying much attention I signed it as the adult who had to confirm Otto’s junior status. Otto unwisely put the postcard on the table outside JHM’s study for it to be posted. Next morning in assembly, after the hymn, reading and prayers, JHM called Otto out to the front of the school and then revealed in somewhat humorous style the nature of Otto’s duplicity. Then to my horror he said: ”And he got an adult to sign it. Come out here, Hawkes.” So there we were out front, facing our grinning schoolmates whilst JHM enjoyed himself regarding the small boy who had entered the competition and the “adult” who had endorsed his entry. This seemed to be the extent of our punishment, a sort of genial humiliation, but JHM decided to push the joke a bit further: “….and so , Kiaow, as an eight-year old cannot possibly be a prefect, you are relieved of your duties immediately.” And that was that. It seems to me that the thought came to JHM on the spur of the moment but, once said, the deed was done and Otto was not reinstated during the term or so before he left, though as I have said he was a popular and reliable chap.

Regarding appointments of teaching staff, JHM could hardly be faulted, though his retention of them was far from satisfactory. I have referred earlier to how few seemed to stay for any length of time, but while they were with us the great majority showed skill and commitment, the main problem for many lying with failures of classroom discipline. One great problem with boarding education can be the possible presence of paedophilia but JHM must have been very shrewd and alert to this menace because, considering the number of staff that he appointed in the nine years I was at the school, I can recall only one or two possibly dodgy characters amongst the staff and I remember only one potentially harmful relationship (not involving a teacher) and that was swiftly terminated. Why most staff remained for such short periods of time is a bit of a mystery. One reason could have been the lack of support over classroom discipline: another must undoubtedly have been that most of our teachers were in their first job and such a small school could not offer promotion to, say, a Head of Department post. JHM could be unreasonable too. Pat Brookes , who went on to make a great contribution to education with a teaching career spent in Africa, told me that JHM got rid of him because of failures of organisation on the trip he arranged to France. As one of the six who went on that blissful fortnight to the Loire region and then to Paris, I was totally unaware of any significant muddles and have always regarded it as the most educational experience of my time at King’s School. How ironic that Pat should get the push for it!

Unsurprisingly, with classroom teaching, JHM himself had no problems with keeping order, but his proficiency as a teacher of English (and RE) was less certain. Questions have been raised about his Bachelor of Arts qualification. When I took “A” level English my instructor was Mr Breach, a history graduate, and I don’t recollect spending much if any time with JHM. I do remember a book he had, a literary history by George Sainsbury which had his name inscribed inside the front cover and the words “York House” written beneath it. Was this a university hall of residence or a teacher training establishment? He obviously enjoyed the English language and revelled in the use of it, particularly in the plays of Shakespeare , the writings of his hero, Winston Churchill and certain passages from the King James Bible, some of which were handed out as impositions to copy out or learn by heart. He did not seem to know much about literature otherwise and in a letter to me he once expressed the view that modern writers deserved “their noses rubbing in a dunghill” which was a pretty sweeping condemnation! His own writing tended to be flamboyant and rhetorical. In one of the Christmas cards he sent to parents he published a short poem of his own which covered the life of Christ in five simple couplets, only one of which I recall:

Now is that richest season that I love,

Now is that glorious tapestry complete:

Now is black Winter’s twisted warp aglow,

Fathered by God Who knows the distant goal

JHM’s lessons had other extraordinary features too. Punctuality was not his strong suit and there were occasions when he wasn’t just late, he didn’t turn up at all. He usually smoked in lessons though I never saw him actually light up in the classroom. His common practice was to start a cigarette, always a long rather exotic brand, just before entering the room and then to consume it right down to a final tiny tab which he would crush out on the blackboard duster with an air of palpable regret. A contemporary claims that he would knock ash into his turn-ups – perhaps they had asbestos linings!

Lessons often formed something of a monologue, a big feature of which would be the often-repeated tales of his sea-faring grandfather. These stories seemed to owe something to the swashbuckling MGM adventure films of the 1930’s and 1940’s, though the existence of said grandfather seems to have been a fact. Scarborough seems to have been the family town and JHM took much pride in his Yorkshire origins. One term we spent an inordinate amount of time on Coleridge’s “Ancient Mariner”. This was due partly to JHM’s poor time-keeping but also to his propensity for story-telling. The AM’s sailing ship gets becalmed in the Doldrums for weeks and so did we. I remember two of the anecdotes. In one the ship’s cook went mad with the heat and cut his throat, whereupon Grandfather seized his wife’s knitting (the wives of sea-captains sometimes accompanied their husbands on lengthy voyages) and there and then used it to close the wound and save the man’s life. On another occasion the heat and inactivity caused the ship’s company to mutiny, led by a gigantic black man. Faced with this insubordination, as they looked up at him from the main deck, Grandfather (who we were told was only a short but powerful man) vaulted the quarter-deck rail and “with a fist as big as a ham” laid the huge black unconscious on the planking. JHM had a relish for such phrases. He was once expatiating on the nature of physical courage and volunteered the example of a boy from his own school days who, although only slightly built, was a tenacious tackler at rugby: “He would even bring me down, sixteen stone of solid bone and muscle…..”

One could go on. These lessons were a bit of an ego-trip for him. He was not an inspiring teacher in any way but there was no trouble in his lessons and he must have imparted something in our handling of the reading and writing of English up to “O” level. As Headmaster, despite his failings, he tried to instil (far from successfully in my case!) Churchillian qualities of courage and determination, independence of thought and self-reliance, a sense of duty and patriotism. Honesty, fair play and good manners were also held up as virtues, though some would question whether the first two were practised quite as much as they were preached. There was also an emphasis on hard work, not least in the frequent quotation of “Anything worth doing is worth doing well.” In the general matter of his management of the school and its affairs, many of us do feel a debt to him. He was certainly not a nonentity!

Other Staff

Who was 'HF'?

I’m reminded of another brave, if not foolhardy act, this time by Alexander Samson, who when I met him at the recent Sherborne re-union after an absence of nearly sixty years seemed to have little recollection of it. Heck, I’ve never forgotten it! We were in the library classroom, the one at the front of the House and next to the church. Old Mosey was taking our English class and at some stage made a remark on the lines of ”Now this reminds me of something that happened to my grandfather.” We snuggled down resignedly to listen to an ancient and improbable tale when suddenly he said, ”What are you smiling at, Samson?” We were listening attentively now, thinking that Alexander would make some fairly mundane and innocuous excuse, but to our horror he replied in a rather languid drawl, “I was just wondering if it was going to be true.”

Aaaaargh!! Death of a most horrible and brutal kind was the least that Alexander might expect from such an act of lese-majesty and we must all have cringed at the prospect of the ensuing mayhem. But then, after a long silence, Mosey spoke in a quiet but rather menacing way: ”Let me tell you, Sampson, that all the things I tell you are true,” and that, astonishingly, was the end of the matter. Mosey’s attempt to reassure us did sound a bit hollow, but I suppose, when one looks back on it, Alexander’s reply did put him in a bit of a spot. A violent response would have destroyed any lingering thoughts in our minds that the tales had some truth in them, which some of them probably did. At any rate I certainly got the impression that for the rest of the year our form at least was treated to fewer of the personal anecdotes than previously.

On this particular afternoon when our game was over and we had changed back into our uniforms, we moved off, as was the custom, in crocodile under the supervision of a teacher. There was a chemist’s shop on our side of Milton Road as we reached it and most staff would wait while anyone interested and in funds went into the shop for the purchase of a bag of Nippits. These were a pretty horrible little throat tablet which in those days of severe sweet rationing gave us some sort of a substitute for the real thing. I don’t know how we got the money, probably from some extra handout from Mum or Dad, because the junior’s weekly allowance was only threepence which could barely purchase our official sweet ration of (I think) four ounces.

But this day, joy! The few who had entered the shop came out exultantly, brandishing to our astonishment foil packages which contained CHOCOLATE! There was an instant melee around the counter and soon we were outside again, all chewing at our lumps of chocolate. They did look a bit unusual, resembling in appearance and composition lumps of brown plasticine but they did have a chocolaty taste. We moved off in crocodile but, very soon, rumours started to spread. We didn’t know quite what the words on the foil wrappers meant but we soon became suspicious that this stuff was designed to “ make you go.” Often in groups of schoolboys there was someone who seemed neglected. He was badly kitted out, never seemed to have pocket-money or anything in the way of tuck and always seemed hungry and, not surprisingly, was usually on the cadge. We had one such boy in our group though I cannot recall his name. This day he couldn’t have believed his luck. Chocolate was soon being offered to him from all directions and he tucked in ravenously, but soon even his suspicions were aroused.

By now the crocodile was moving pretty quickly. I doubt whether the “chocolate” was anything like as effective as we imagined but such were the forces of auto-suggestion that most of us were experiencing an urgency to get back to school as soon as we could. A right turn took us off Milton Road and up a steep winding path through a cemetery. Usually after an hour’s football we nine year-olds would be tired and the teacher would have to cajole our flagging efforts. Today he didn’t have to bother. The crocodile tore up the hill like a steam train with our teacher struggling to keep in touch. When we reached the long level straight of the Lower Bristol Road that led to the junction near Arundel Road where Kingsholme School was situated, all semblance of order or decorum was lost and the tidy crocodile became a stretched- out file of runners with the Ragged One clearly in the lead. Soon we were in the welcome haven of the bogs but, as there were only about four cubicles, most of us were reduced to hopping from one foot to the other, imploring our luckier comrades to hurry up. I don’t think anyone had any sort of an “accident” over this matter but it does illustrate the powers of suggestion and I have often wondered at the cynicism of the pharmacist who had let us spend our cherished pennies in this way. I can’t remember who the teacher was but he seems to have been a bit naïve or negligent, or was he simply in a hurry to get back to the Staffroom?

A term or two later a young football coach called FRANK TWISTLETON was engaged to give us some instruction in the basics of soccer.

JACK HOLT, a former Kingsholme pupil, came to open the swimming-pool officially at the 1949 Exhibition weekend. He had represented Great Britain at the 1948 London Olympics. He swam a few impressive lengths and later, not surprisingly, won the Visitors’ Cup, his brother MICKY, another Old Boy, being the runner-up.

Sometime in 1952 the BISHOP OF GLOUCESTER came to confirm about eight K.S. pupils in Sherborne Church.

Also that year, in the summer, NICK STACEY came for a few hours to tell us about relay change-overs. He had been a member of the Oxford University 4x400 metres team which had been selected to represent Britain in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. They were certainly finalists (something tells me they won silver) and I believe much of their success was due to the dedicated way they had developed their change-over technique. Our house and school relay teams certainly benefited from his advice. Nick Stacey came to us at the invitation of a university friend who was at the time (and only briefly) the vicar of Sherborne. After a very busy period as a churchman in the diocese of Southwark, Nick Stacey became a prominent social activist and head of social services in Kent.

Howard Read joined the school in 1952/3. His father AL READ, who had been a successful businessman in the North West, had almost by chance got into the world of entertainment and became probably the best-known radio comedian of his era. In those days of austerity he had a most impressive American (?) car. There is a brief glimpse of it on one of the school films. Engraved on the central motif of the chrome radiator was his famous catch-phrase (Lancastrian accent essential): ”Right,monkey.”

However, the most famous visitor in my opinion was not a human being at all. It was in fact the proto-type of the mighty BRISTOL BRABAZON airliner, the only one that ever flew. Do look it up on Wikipedia. The Chief Test Pilot was Bill Pegg but his assistant was E.H. Statham, Richard’s father, and on the day in question, 1st March 1950 , he seems to have been in charge and brought the monster – as it seemed in those days – over the front of the school. I think he must have timed it for a break or lunchtime because I was on the front field and remember it coming very low and slowly from I think the direction of the lake. I well recall the bass rumble of its engines. It’s all in the genes, they say: Richard’s career was spent in the RAF as a fast-jet flier. The Brabazon had already had an impact on my life. A few years earlier they had had to extend the runway at Filton to accommodate its needs which meant demolishing a small settlement called Charlton and re-routing the Bristol to Weston-super-Mare road which we used when going to or from Kingsholme at holiday time.

I was terrible at trying to keep a diary but for a brief period managed to do so in the Jan-March term 1950. I've always kept it, probably because of its rarity for me! The entries are nearly all very boring though they do mention our exclusive fly-past by the Bristol Brabazon on March 1st. It is a Letts Schoolboys diary and on the Pocket-money page I have recorded 24 shillings paid into the school by my father at the beginning of term, but only 12 shillings received by me through the weekly issues of 1/6d. I wonder what happened to the rest as Dad put in another 26 shillings for the summer term!

Mind you, James Mosey did get us some good films that term: The Black Sheep of Whitehall (Will Hay); Oliver Twist; Scott of the Antarctic; The Way Ahead; The Silver Fleet; Pittsburgh; The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp.

Itinerary

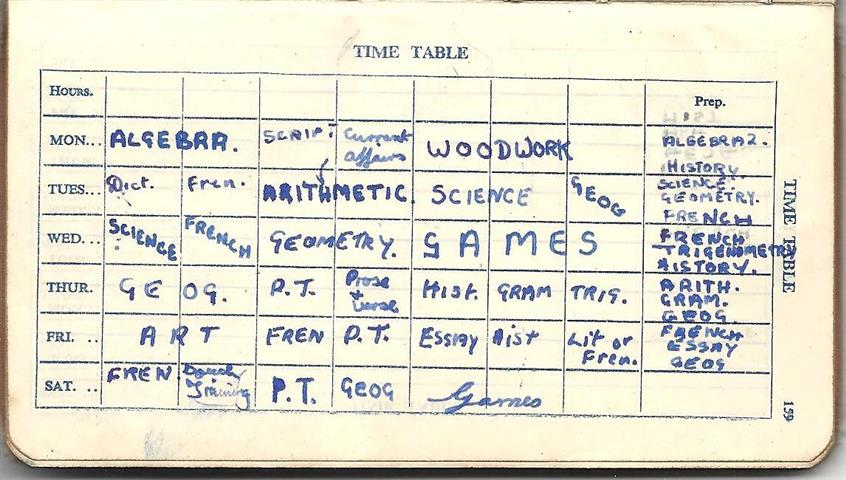

We also had Saturday morning lessons and please remember what I mentioned in my Anecdotes [above] that some winters the timetable was adjusted so that we had extra compulsory games or other activities in the afternoons Mon-Fri but still had seven x 45 minute periods a day!

1950 Time Table

We also had Saturday morning lessons and please remember what I mentioned in my Anecdotes that some winters the timetable was adjusted so that we had extra compulsory games or other activities in the afternoons Mon-Fri but still had seven x 45 minute periods a day!

My diary also reminds me that each term we had one week of dining-room service to do and another week of washing-up (under George and Stan's supervision). How did anyone find the time to get into trouble! Weekends, perhaps.

Academic

On the academic side the school had serious failings, some of which may have been remedied after I left. In particular science provision was deplorable. I remember very little equipment not even a microscope, in the so-called laboratory. Only General Science was taken at "O" level. The exam required no practicals and hardly anyone regarded it seriously so that even a borderline pass was a rarity. In most other subjects our education did not compare too unfavourably with what the State offered in the smaller grammar schools and many secondary moderns.

Part 2

For the many of us who enjoyed games, opportunities and facilities, apart from the absence of a proper gym, were excellent. The Sportsmaster was usually a Loughborough graduate. As the school was so small (about 120 boys between the ages of 7 and 18) one had every chance of getting into a team and there was a full programme of fixtures for soccer, hockey and cricket, mainly against Gloucestershire grammar schools. Teams sometimes took a hammering against larger schools with big Sixth Forms, like the Crypt School, Gloucester, but on the whole results were not bad. The cricket team was once dismissed by Burford for only 6 and once during a fielding session when several catches were dropped. JHM was incensed enough to invade the outfield and roar, "Do you all want buckets?" Against adult teams at hockey (e.g. the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester), JHM and other staff would play. Needless to say, we had a splendid cross-country course devised by Geoff Perry, though it could be an agonising experience for participants. The swimming-pool was a great source of pride, especially as pupils provided much of the unskilled labour during its construction in the late 40's. Those who could swim enjoyed this unheated facility though I'm not sure how many actually learnt to swim in it.

Part 3

The school was very tightly organised and disciplined. The only serious indiscipline I remember - and there was plenty of it - was in the lessons. Elsewhere, all other activities were potentially under the responsibility of JHM who could quell a rowdy commonroom simply by clearing his throat as he approached. One has to acknowledge also that JHM was occasionally guilty of unforgivable outbursts of anger in which he could assault boys over relatively minor misdoings. Indeed, much of the awe in which he was held arose from the use of corporal punishment. I don't think that by the standards of the time this happened excessively and in my nine years at the school I recall only one occasion on which there was a public caning, though this runs counter to another's recollections.

Part 4

There were occasionally the humiliations of being hauled to the front of assembly for public castigation and there was one unforgettable occasion when a punishment resulted in the complete rout of JHM himself, as follows.

Part 5

Physically most of us seemed to thrive under the regime though government rationing took some time to end and food provision was not generous. Parents may have been impressed by the fresh vegetables in the kitchen gardens but most produce probably went to market. To my knowledge JHM owned a greengrocer's business in Cheltenham in the mid-50's and we partook of the produce only when there was e.g. glut of lettuce. One year enormous baked potatoes with skins like tree bark were introduced and within a few weeks five boys had appendectomies. The serving of such potatoes was discontinued though it is possible that the cause of the trouble was psychosomatic - Kathleen Mosey had been very ill after such an operation during the preceding school holiday.

Part 6

Nurses and Other Staff

It occurs to me that many questions concerning identities of staff or pupils in the early 50’s could be resolved by resort to the school photos on the website and their very valuable lists of names. A recent visit to the 1950 photo brought me a surprising discovery: why on earth did we have no fewer than three nurses that term? No wonder Peter Pfaff had the time to conduct a successful courtship of the fair Nurse Langeth! What a pity that it had all to end so tragically. Pete’s crash occurred circa 1952-3. I remember Dickie Moore (PE) telling me of it one evening around 9.30 (senior lights-out). He was pretty cut up. I cannot vouch for this, but a year or two afterwards I was told that a child was born soon after Pete’s death and that subsequently his widow was seriously unwell. I didn’t learn the nature or outcome of the illness. I just hope that, if I was informed correctly, she managed to make a full recovery and that in time she found some measure of happiness… and that if indeed Pete did have a child (well over 50 now!) he or she might have learnt, not least from this website, what a truly great chap Peter Pfaff was. It is especially moving that in the 1950 picture Pete seems to be making a comment out of the side of his mouth that his-wife-to-be is finding amusing. I wonder what it was.

Part 7

James Mosey was a contradictory personality. He could be genial and even kind and sympathetic on occasion, but could easily fly into a nasty rage, occasionally completely losing his temper. He once came quietly into the room to the left of the front entrance which at that time contained a large billiard table. Some boys had been whizzing a ball forcefully across the baize surface by hand, a practice strictly forbidden but rather fun. He came silently through the door from the Hall and all but one of us froze as we saw him. Jimmie Shelley, a very pleasant mild-mannered lad who was about 15 at the time, had his back to the door and was unaware of his presence. JHM watched him quietly for a few seconds as he whipped the ball across the table and then suddenly leapt forward and kicked him violently with the pointed toe of his shoe at the very base of his spine. Jimmie went down writhing and I well remember the look of mixed agony and astonishment on his face as he fell and, turning saw who his assailant was. JHM may have thought he had gone too far this time as no further punishment was meted out. Jimmie did not seem to suffer any lasting effects from the assault but that was simply a matter of luck.

Down to the ditch drag him – in state!

When tented grain is camped upon the hills

And golden-steepled stacks each rickyard fills

And morning mists upon the meadows move.

Slow Summer’s light-spun gold, gay Spring’s lithe green,

With scarlet berries where the flowers were seen

And waves of pearl where night and morning meet.

Its fabric strongly woven when the snow

Hid the brave growth beneath the labouring Earth;

As one impaled on pain mistakes the birth

And lovely flowering of the immortal soul.

There’s no time to go into details on other members of staff and other OB’s will have different views – not least on JHM himself – but I look back with gratitude and even a touch of affection on: Peter Pfaff (English), Kate Mosey herself (Maths and Art), Dickie Moore (PE), Geoff Perry (Maths and Science), Pat Brookes (French), CA Benn (Maths), HC Burnell-Jones (French and Latin); and I remember as very reliable and consistent: DJ Thompson (History and the Scouts), GA Evans (English), RW Breach (History and English), F Nicholas (Geography), Wat Tyler (Maths), and who didn’t have a soft spot for old Chaddie (Science)?

Part 8

Several people have asked me who was the HF who endured a public caning from James Mosey with such notable stoicism. Those of us who were there will know the answer and, though I don’t have his permission, I can’t think that it does him anything but credit when I reveal that it was Henry Forti.I believe that Henry has been in touch with the KS website in the last year. He is a professional actor, stage name Jonathan Burn . Perhaps his acting career began on that day: he gave no sign that it hurt!

Alexander Samson questions the authenticity of JHM's stories

Back in Kingsholme

My funniest experience (in retrospect) occurred when we were still at Kingsholme School in Weston-super-Mare. I must have been about nine at the time. All the school had Games on the Wednesday afternoon and the juniors had their game of football first. It was held in a rented field some distance from the school down a short lane off Milton Road. In more recent years a firestation occupied the site, though I don’t think it is still there. Part of the playing area was crossed by some noticeable undulations that were caused by faulty drainage arrangements, and a deep water-filled ditch ran alongside one touch-line from which the ball had sometimes to be rescued with the aid of a long stick. We changed in a large windowless shed, the target of much vandalism by the locals, and which was filled with heaps of old netting and rope. Any forays into the interior could reveal strange sights and revolting smells so we tended to stay just inside the door.

Notable Visitors

Over my years at the school we had a few notable visitors. In summer 1949 W.R.GREGSON came for about a week or two to teach us the rudiments of stroke play in cricket. We were drilled en masse on stance, backlift, forward play, back play etc. He was a keen advocate of lifting the bat to face towards point rather than the conventional straight backlift which has the face pointing backwards towards the wicket-keeper. He thought that the bat came down more naturally into the playing straight position and I must say that it seems to me he had a point (no pun intended) and I always followed his advice, not that my batting career was much of a recommendation! He must have told us a few things about bowling and fielding but I don’t recall anything specific. Gregson must have been well into his sixties with a shock of white hair but he was as brown as a berry, very fit and he would take a swim in the lake most mornings before breakfast. His record can be found in the earlier Twentieth Century Wisdens. He played professionally for Lancashire and was said to have had a trial for England. He performed a hat-trick against Leicestershire in 1906. He may have played as a young man against WGGrace whose first-class career extended to 1908.

Daily Itinerary and Timetable, 1950

07.20: wake-up bell.

07.50: queue in the Hall to await breakfast gong.

08.00: breakfast followed by bed-making.

c.08.50: registration in form-room followed by Morning Assembly in the Hall.

c.09.20: two x 45 minute lessons.

c.10.50 break time.

c.11.10: two x 45 minute lessons.

c.12.40: queue in the Hall to await lunch gong.

c.12.45: lunch followed by some free time. I don't recall an afternoon registration.

c.14.00: three x 45 minute lessons, possibly split with a short break between the sixth and seventh lessons.

c.16.30: queue in the Hall to await gong for high tea.

c.16.40: high tea followed by some free time.

c.18.00: Prep in form-rooms supervised by prefect. 30 mins per prep. 4B had 3 preps Mon-Fri.

c.19.30: if 3 Preps. Free time. [I imagine only one Prep for the juniors or they would not have had any evening free time. Ed.]

Bed-times depended on your age: juniors at 19.00 but I think even the oldest boys had to go to their dormitory at 21.00 for lights-out at about 21.30.